Hello all:

Thank you for the

communication. The City has not established the governing board for the

Black Arts Movement and Business District pursuant to the resolution

that named the District. The City Administrator and City Attorney are

preparing a report to come back to the Council with legal options and

alternatives. My staff and others in the administration have also begun

to explore grants and philanthropy to support the effort.

In the meanwhile, we recognize

that the Black Arts Movement artists and others continue to hold

independent community meetings to discuss/brainstorm/plan ideas and

independent actions in support of the District.

As soon as the Administration

completes its report, my office will reconvene the Black Culture Keepers

meetings that we hosted as part of the community outreach leading up to

the adoption of the Resolution. I am hoping to reconnect

no later than July.

Thanks much, Lynette

Alessia Brisbin on upcoming Culture Keepers Meeting, Tuesday, July 26, 6-8pm, Oakland Center Cultural Center, 14th and Adeline

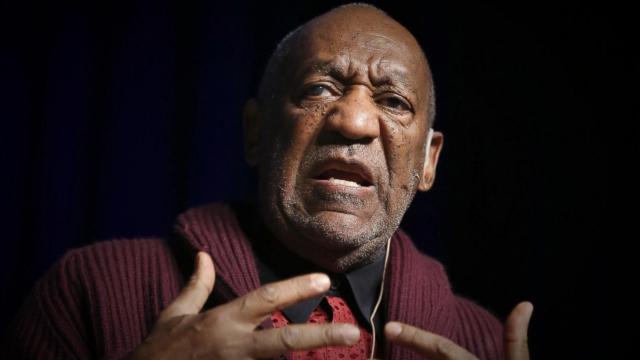

BAMBD co-founder Marvin X and Lynette McElhaney, President, Oakland City Council

photo Adam Turner

Alessia Brisbin on upcoming Culture Keepers Meeting, Tuesday, July 26, 6-8pm, Oakland Center Cultural Center, 14th and Adeline

Good Evening,

Please save the date for the next Culture Keepers meeting to be held at the Oak Center Cultural Center on Tuesday, July 26th from 6:00pm-8:00pm.

The Council President would like to take this

opportunity to follow-up from the last meeting and identify next steps

for the businesses and artists in the corridor.

I will send out a calendar invitation shortly, please confirm your attendance at your earliest convenience.

If you have any questions at all please feel free to either call or email me.

Thank you for your support.

Best,

Alessia Brisbin

Assistant to Council President Lynette Gibson McElhaney

| ||||

| ||||

Sunday, May 22, 2016

We

cannot engage in this BMBD project without thinking and planning long

term, i.e., for the next 25 to 50 years. I have indicated in my remarks

on the Harlem Black Repertory Theatre: how and why it was de-funded by

the US government once they saw the radical agenda in the music, plays

and poetry, not to mention the internal flaws that included violence

(BAM philosopher Larry Neal was shot by psychopathic artists). The death

of Baraka’s Harlem project forced him from Harlem back to his native

Newark. While in Newark he reconstructed the BART into a cultural center

called Spirit House. But Spirit House soon transcended art and culture

into

the political realm, e.g., a group was formed called The Committee for

Unified Newark, if I’m correct. It worked to build housing, economic

projects and political engagement.

As

I think about BAMBD and how it can endure for the next 25 to 50 years,

it seems to me BAMBD must extend into the political realm. Otherwise, we

will be at the whim of reactionary politicians and the black

bourgeoisie culture police mortally afraid of “the Movement” and “black

power” among other psycholinguistic items in their world of make

believe.

When

Baraka and his associates entered Newark politics (of course Amiri

Baraka also organized on the national level, e.g., the Congress of

African People brought ten thousand people to Gary, Indiana, 1972 for a

convention) and eventually got the first

black mayor elected, Kenneth Gibson, they immediately discovered

they had supported a Trojan house. Baraka told me Gibson had sold out

before inauguration day to Newark’s massa Prudential Insurance. So even

if and when we enter local politics, we must be ever on the alert not to

waste precious time and energy on rats. Baraka continued supporting the

black mayors and every one of them was corrupt and did time in jail

and/or prison. Finally, his son Ras Baraka, won the mayorship and is

doing a job worthy of praise, according to the New York Times and his

mother, Amina Baraka, with whom we are in communication with as per

lessons BAMBD can learn about art and politics, especially since Newark

is a city much like Newark although we doubt Newark is facing the level

of gentrification in Oakland.

BAMBD

must consider entering the political arena, electing people to the

planning committee, city council, including the mayor’s office. It is

not enough to be solely “artists” and cultural workers willing to accept

mini grants from the City. I cannot stress enough BAMBD must be an

independent entity. We should therefore keep our ties to city hall to a

minimum because we cannot assume a positive relationship will not change to negative

with the political winds, especially if we don’t have people in

positions of political power.

As per Oakland, OCCUR is an example of

what I’m describing. OCCUR, a non-profit organization founded by Paul

Cobb, later directed by David Glover (RIP). Under

city funding for years, OCCUR is now being de-funded by the city and

will probably dissolve as an organization. For sure, after decades as a

non-profit organization, OCCUR should be self-sustainable by now rather

than facing dissolution due to non-funding by the City of Oakland.

FYI, we recently heard Black theatre groups in New York City have been de-funded.

BAMBD must be wise enough to think ahead about all possible pitfalls, from internal flaws to external events and other factors but especially such stinking thinking as getting tied to the umbilical cord of Oakland politricks for an ephemeral ride to nowhere. Think of a billion dollar trust fund, independent and for community benefit, not controlled by city government or individuals.

—Marvin X

Eric Arnold

Tuesday, May 24, 2016

BAMBD must consider entering the political arena,

electing people to the planning committee, city council, including the

mayor’s office. It is not enough to be solely “artists” and cultural

workers willing to accept mini grants from the City. I cannot stress

enough BAMBD must be an independent entity. We should therefore keep our ties to city hall to a minimum

because we cannot assume a positive relationship will not change to

negative with the political winds, especially if we don’t have people in

positions of political power.--MARVIN X

I

agree that BAMBD should be a factor in politics and policy. However,

what you are suggesting entails developing a greater, not lesser,

relationship with City Hall. The tricky part is maintaining a degree of

autonomy, since the reality is that we need City Hall, and we have to

show them that they need us.

My

counsel is not to take an overly-antagonistic stance toward the powers

that be, but rather work to become ubiquitous to the process of

determining Oakland's future. That means developing a policy platform

which is as realistic and pragmatic as it is ambitious and visionary.

Romanticizing grassroots efforts may result in failure to cultivate the

type of major economic investment which is necessary for BAMBD to be a

success. BAMBD should be a $20, $50, $100 million initiative worhty of

investment by philanthropic and corporate entities. Not to say that

grassroots efforts aren't important, but the game being played now is

not for small marbles.

The

most obvious thing is that 5 Council seats are up for re-election in

2016. The election is jsut a few months away. We should be thinking

about how to leverage this to further our platform. Also, Planning

Commission seats are not elected, but rather appointed.

Our

immediate next-step actions should be establishing a Steering Committee

and subcommittees, and generating implementable recommendations, as

well as collecting data which makes the case for economic investment as

part of a cultural retention strategy. This includes mapping cultural

assets as well as economic assets withing the footprint, and negotiating

for cultural benefits with any new developments within the footprint.

BAMBD

needs a Business Improvement District (BID) association. That’s who

paid for the banners that are in Uptown- The Uptown-Lake Merritt

Business Association.

These BID associations are also nonprofit arms that an apply for grants

and other subsidies. It makes it easier to raise funds. The California

Arts Council’s Business District initiative has NO FUNDS attached to it

right now. There is no commitment for funds,

so we have to find other means to raise money. There are granting

agencies that give funds to BIDs.

Denise Pate

Cultural Funding Program, Coordinator

Cultural Arts & Marketing, Department of Economic and Workforce Development

City of Oakland

1 Frank Ogawa Plaza, 9th Floor

Oakland, CA 94612

510-238-7561 office

510-238-6341 office

dpate@oaklandnet.com

You may have noticed three recent occurrences that have me thinking about an idea and strategy I had 20 years ago that Black people in Oakland are still struggling to bring to fruition.

Mao on Petty-bourgeois ideas

Among the proletariat many retain petty-bourgeois ideas, while both the peasants and the urban petty bourgeoisie have backward ideas; these are burdens hampering them in their struggle. We should be patient and spend a long time in educating them and helping them to get these loads off their backs and combat their own shortcomings and errors, so that they can advance with great strides. They have remoulded themselves in struggle or are doing so, and our literature and art should depict this process. As long as they do not persist in their errors, we should not dwell on their negative side and consequently make the mistake of ridiculing them or, worse still, of being hostile to them. Our writings should help them to unite, to make progress, to press ahead with one heart and one mind, to discard what is backward and develop what is revolutionary, and should certainly not do the opposite.

The Problem of Audience

I began life as a student and at school acquired the ways of a student; I then used to feel it undignified to do even a little manual labour, such as carrying my own luggage in the presence of my fellow students, who were incapable of carrying anything, either on their shoulders or in their hands. At that time I felt that intellectuals were the only clean people in the world, while in comparison workers and peasants were dirty. I did not mind wearing the clothes of other intellectuals, believing them clean, but I would not put on clothes belonging to a worker or peasant, believing them dirty. But after I became a revolutionary and lived with workers and peasants and with soldiers of the revolutionary army, I gradually came to know them well, and they gradually came to know me well too. It was then, and only then, that I fundamentally changed the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois feelings implanted in me in the bourgeois schools. I came to feel that compared with the workers and peasants the unremoulded intellectuals were not clean and that, in the last analysis, the workers and peasants were the cleanest people and, even though their hands were soiled and their feet smeared with cow-dung, they were really cleaner than the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois intellectuals. That is what is meant by a change in feelings, a change from one class to another. If our writers and artists who come from the intelligentsia want their works to be well received by the masses, they must change and remould their thinking and their feelings. Without such a change, without such remoulding, they can do nothing well and will be misfits.

Many comrades concern themselves with studying the petty-bourgeois intellectuals and analysing their psychology, and they concentrate on portraying these intellectuals and excusing or defending their shortcomings, instead of guiding the intellectuals to join with them in getting closer to the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers, taking part in the practical struggles of the masses, portraying and educating the masses. Coming from the petty bourgeoisie and being themselves intellectuals, many comrades seek friends only among intellectuals and concentrate on studying and describing them. Such study and description are proper if done from a proletarian position. But that is not what they do, or not what they do fully. They take the petty-bourgeois stand and produce works that are the self-expression of the petty bourgeoisie, as can be seen in quite a number of literary and artistic products. Often they show heartfelt sympathy for intellectuals of petty-bourgeois origin, to the extent of sympathizing with or even praising their shortcomings. On the other hand, these comrades seldom come into contact with the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers, do not understand or study them, do not have intimate friends among them and are not good at portraying them; when they do depict them, the clothes are the clothes of working people but the faces are those of petty-bourgeois intellectuals. In certain respects they are fond of the workers, peasants and soldiers and the cadres stemming from them; but there are times when they do not like them and there are some respects in which they do not like them: they do not like their feelings or their manner or their nascent literature and art (the wall newspapers, murals, folk songs, folk tales, etc.).

Nevertheless, no hard and fast line can be drawn between popularization and the raising of standards. Not only is it possible to popularize some works of higher quality even now, but the cultural level of the broad masses is steadily rising. If popularization remains at the same level for ever, with the same stuff being supplied month after month and year after year, always the same "Little Cowherd" [6] and the same "man, hand, mouth, knife, cow, goat", [7] will not the educators and those being educated be six of one and half a dozen of the other? What would be the sense of such popularization? The people demand popularization and, following that, higher standards; they demand higher standards month by month and year by year. Here popularization means popularizing for the people and raising of standards means raising the level for the people. And such raising is not from mid-air, or behind closed doors, but is actually based on popularization. It is determined by and at the same time guides popularization. In China as a whole the development of the revolution and of revolutionary culture is uneven and their spread is gradual. While in one place there is popularization and then raising of standards on the basis of popularization, in other places popularization has not even begun. Hence good experience in popularization leading to higher standards in one locality can be applied in other localities and serve to guide popularization and the raising of standards there, saving many twists and turns along the road. Internationally, the good experience of foreign countries, and especially Soviet experience, can also serve to guide us. With us, therefore, the raising of standards is based on popularization, while popularization is guided by the raising of standards. Precisely for this reason, so far from being an obstacle to the raising of standards, the work of popularization we are speaking of supplies the basis for the work of raising standards which we are now doing on a limited scale, and prepares the necessary conditions for us to raise standards in the future on a much broader scale.

l

l

Sonia Sanchez, Lakiba Pittman, Kim McMillon and Marvin X

Contact Info:

THE MOVEMENT

PEOPLE'S NEWSLETTER OF THE BAMBD

Contact the Editor: Marvin X

Welcome to Africa Town: 20 Years After the First Attempt to Create a Black Arts and Cultural District in East Oakland

You may have noticed three recent occurrences that have me thinking about an idea and strategy I had 20 years ago that Black people in Oakland are still struggling to bring to fruition.

In 1996-97 I ran a book shop and incense/body oil, African Import and Export shop on 76th and MacArthur Blvd. in Oakland. I learned at the time that the area between 73rd and MacArthur, East to 90th and MacArthur, and North from MacArthur to Bancroft in Oakland, CA had been targeted by the federal government as only ONE OF EIGHT CITIES in the United States designated as an EMPOWERMENT ZONE.

It was called the E-MAC district also known as the CASTLEMONT CORRIDOR. There were millions of dollars targeted toward the area for development. The difference between an ENTERPRISE ZONE such as the area on San Leandro Blvd. and 85th Avenue, or the enterprise zone on Hegenberger Road which stretches from San Leandro through to the Oakland Airport, is that an EMPOWERMENT ZONE and all of the community development block grant dollars sent to that zone can be used for COMMUNITY AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT and not just business development.

My idea at the time was to establish the area of MacArthur from 73rd to 82nd as an Afro-Carribean themed area. We would all paint the fronts of our stores either red, green,black or gold and the billboard on top of COLOR ME NATURAL would be purchased and state proudly WELCOME TO AFRICA TOWN!

Now to the three recent occurrences: There was recently a meeting of individuals and groups in East Oakland around the establishing of BAMBD (Black Arts Movement Business District) on May 13,2016, and here will be further town hall style meetings for this, one scheduled in June 13, 2016 at the Eastside Arts Alliance, 2277 International Blvd, Oakland, CA . I am encouraged by this and sure enough, the progenitors of this recent thrust to establish a BAMB district are people who were around me at the time I had the idea to work to form one in 1996.

One thing to note: There’s no reason to re-invent the wheel. The work to establish the BAMB district along the Castlemont/E-MAC should continue because this area is one OF ONLY EIGHT AREAS IN THE ENTIRE COUNTRY designated as an EMPOWERMENT ZONE and there must have been a good reason for that. Keep in mind that Empowerment Zones are certain urban and rural areas where employers and other taxpayers qualify for special tax incentives. This designation alone makes the Castlemont corridor an ideal spot for a BAMB. More importantly, the demographics of this area make it the de facto Africa Town. It is actually the last area that has not been gentrified to the point that so many other Oakland areas have. So think about this area first when considering where to establish a BAMBD.

However, another recent occurrence that is either a blessing or a curse is the recent fire which gutted the entryway to the E-MAC/Castlemont corridor (See photograph above. This area will now have to be rebuilt. The question is, who will benefit from the rebuilding effort? I’m sure that traditional developers in the city are chomping at the bit to get their paws on the area. Some are already saying that the long term goal of typical Oakland gentrifier-developers may HAVE SOMETHING TO DO WITH HOW THAT BLAZE GOT STARTED IN THE FIRST PLACE!

Be that as it may, the destruction of those buildings at the entryway to the corridor is either a blessing or a curse and what will determine either will be which steps are taken to stake a claim for that area. As I have stated above, that claim was staked by me and a few others 20 years ago in 1996. Bill Clinton was president at the time and it was his administration that designated that area as an Empowerment Zone.

Which brings me to the other occurrence which came to mind. Those millions of dollars targeted to that area WAS NEVER SPENT. If those millions of dollars that were targeted to the area are still there, Hillary Clinton, Bill Clinton’s wife is running for president. If she is elected, I’m sure she can ask Bill where that money is.

Marvin X on Black Bourgeoisie Art and Opportunism

The

Black Bourgeoisie is known for its opportunism and exploitation of

Grass Roots culture or the culture and art of the masses. There is often

no mention of Marcus Garvey Movement's critical influence on the Harlem

Renaissance by spreading Black consciousness, publishing poetry in his

newspaper and otherwise influencing North American art and culture.

In

the 60s, it was the Nation of Islam vie the Honorable Elijah Muhammad

that moved us from Negro to so-called Negro to Black to Aboriginal

Asiatic Man. Most academic "tenured Negro" scholars focus on Malcolm X

as the chief influence on the Black Arts Movement, relegating Elijah

Muhammad to a minor role. Alas, who was Malcolm's leader and teacher?

This myopia of understanding is partly due to what Harold Cruse called

The Crisis of Black Intellectuals (see his book by the same name). This

was much more than an intellectual crisis but a spiritual crisis very

similar to the grief Shia Muslims over the assassination of their imams,

expressed in their ritual of suffering. In short, Black intellectuals

and the Black community in general has not recovered from the death of

Malcolm X and the role of the Nation of Islam in his murder, although

little emphasis is put on the role of the American government in his

murder.

As

a result, in intellectual and academic circles, the Nation of Islam's

influence is downplayed as per the Black Arts Movement. Sadly, it took a

Near Eastern American Islamic scholar, the Syrian Dr. Mohja Kahf, to

delineate the fundamental role of the Nation of Islam in the Black Arts

Movement and the genre she calls Muslim American literature.

So

we move from the Black Arts Movement's fundamental influence by the

Nation of Islam--and its progenitor, the Marcus Garvey Movement, to the

Black bourgeoisie's interpretation of Black Art, usually a Miller Lite,

World of Make Believe (E. Franklin Frazier's Black Bourgeoisie) version

of art, devoid of artists as artistic freedom fighters.

In

the 60s, the government, foundations and corporations, supported their

version of Black Art with grants going to such commercial projects as

the Negro Ensemble Company. They tolerated the New Lafayette Theatre in

Harlem (of which I was a member as associate editor of Black Theatre

Magazine). But ultimately the New Lafayette was defunded when it was

clear it was only a step above the Black Arts Repertory Theatre founded

by LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka. Of course, Black Arts Repertory Theatre was

defunded when its message of Black liberation was clear. As we know,

Amiri Baraka departed Harlem and returned home to Newark, NJ, and

founded Spirit House, the resurrection of the Black Arts Repertory

Theatre.

Meanwhile,

the aesthetics of the Black Arts Movement was watered down and

opportunists from the movement went commercial, including many BAM

actors who moved into film and television, i.e., the Blackexploitation

genre that basically persists until today, no matter films such as

Malcolm X, Selma, 30 Years A Slave, the Butler, et al.

There

has been no film utilizing the Muslim myth of Yacub, although Amiri

Baraka adapted the myth in his drama A Black Mass. The closest we come

to a film utilizing original North American African mythology is Sun

Ra's Space is the Place. Sun Ra is the Pope of the Black Arts Movement,

Amiri Baraka its High Priest. Sun Ra is considered the father of the

genre Afro-futurism, Octavia Butler, the mother. We are thankful members

of the conscious Hip Hop recognizes Sun Ra but we doubt Hip Hop

understands he is the Pope of BAM.

Although

BAM provided the literature (see the anthology Black Fire, edited by

Amiri Baraka and Larry Neal), for the Black Power Movement and Black

Studies, BAM literature was considered too radical for academia, thus

BAM literature was suppressed and those initial radical teachers in

Black Studies were removed and replaced by more pliant "tenured Negroes"

who remain today. Many now recognize the fundamental contribution of

the Black Arts Movement to Black Studies, Gender Studies, Chicano

Studies, Native American Studies, et al. "Just don't bring them Black

Arts Movement nigguhs to campus. We glad most them nigguhs is dead so

they can't tell the truth on our punk asses who only wanted a job with

no connection to Civil Rites (Sun Ra term) or Black Liberation. See

Cecil Brown's Hey, Dude, What Happened to My Black Studies?

Ironically,

the schizophrenia of the Black Bourgeoisie is evidenced when one visits

their homes filled with Black Arts Movement radical art, especially the

art of BAM's queen Mother, Elizabeth Catlett Mora. It's truly amazing

how the Black Bourgeoisie try to separate her from the Black Arts

Movement. Perhaps, very similar to how the Black Bourgeoisie try to

separate Gwen Brooks from BAM, although no one can speak of the Chicago

BAM without noting the mentoring role of Gwen Brooks (RIP).

In

the modern era, we must note the Atlanta Black Arts Festival is the

prime example of the Black Bourgeoisie usurpation of BAM. Initially, the

Atlanta Black Arts Festival acknowledged and included members of BAM in

the festival, but not of late, it is a full blown Black Bourgeoisie,

world of make believe event.

We

suspect Oakland's Black Arts Movement Business District is headed to

Black Bourgeoisie heaven, i.e., the world of make believe. After many

months, we yet see the Black Liberation flag flying along the 14th

Street corridor. We yet see North American African vendors along the

streets of the corridor as economic self-sufficiency in the Marcus

Garvey/Elijah Muhammad tradition of do for self. We yet see the SRO

hotels in the district transferred into land trusts for the members of

the district, artists, workers and common people, many of whom live on

the precipice of homelessness and dual diagnosis, i., mentally ill and

suffering drug abuse as victims of pervasive global white supremacy.

Let's be clear, global white supremacy is not all white, alas, it can be

Asian, African, Arab, Latin, etc.

For

those who suffer the low information mentally, be informed, BAM was/is a

national movement of liberation and shall remain such. The Black

Bourgeoisie puppets of globalists, developers and gentrifiers need to

take a hike for the peoples of the world are moving into the corridor of

beauty and truth. Ugliness has no place in the movement of beauty and

truth.

On the 50th anniversary of the Oakland founded Black Panther

Party, we ask: are you part of the problem or part of the solution?

Black Panther Party Co-founder Dr. Huey P. Newton meeting

Chinese Premier Chou En Lai in China

Black Panther Party leaders Elaine Brown and Eldridge Cleaver with American delegation meeting General Giap, the man who defeated the USA in Vietnam.

Chairman Mao greeting Shirley Graham DuBois and

Dr. W.E.B. DuBois in China

Chinese Premier Chou En Lai in China

Black Panther Party leaders Elaine Brown and Eldridge Cleaver with American delegation meeting General Giap, the man who defeated the USA in Vietnam.

Chairman Mao greeting Shirley Graham DuBois and

Dr. W.E.B. DuBois in China

TALKS AT THE YENAN FORUM ON LITERATURE AND ART

Mao Tse-Tung

May 1942

INTRODUCTION

May 2, 1942

Comrades!

You have been invited to this forum today to exchange ideas and examine

the relationship between work in the literary and artistic fields and

revolutionary work in general. Our aim is to ensure that revolutionary

literature and art follow the correct path of development and provide

better help to other revolutionary work in facilitating the overthrow of

our national enemy and the accomplishment of the task of national

liberation.

In

our struggle for the liberation of the Chinese people there are various

fronts, among which there are the fronts of the pen and of the gun, the

cultural and the military fronts. To defeat the enemy we must rely

primarily on the army with guns. But this army alone is not enough; we

must also have a cultural army, which is absolutely indispensable for

uniting our own ranks and defeating the enemy. Since the May 4th

Movement such a cultural army has taken shape in China, and it has

helped the Chinese revolution, gradually reduced the domain of China's

feudal culture and of the comprador culture which serves imperialist

aggression, and weakened their influence.

To

oppose the new culture the Chinese reactionaries can now only "pit

quantity against quality". In other words, reactionaries have money, and

though they can produce nothing good, they can go all out and produce

in quantity. Literature and art have been an important and successful

part of the cultural front since the May 4th Movement. During the ten

years' civil war, the revolutionary literature and art movement grew

greatly.

That

movement and the revolutionary war both headed in the same general

direction, but these two fraternal armies were not linked together in

their practical work because the reactionaries had cut them off from

each other. It is very good that since the outbreak of the War of

Resistance Against Japan, more and more revolutionary writers and

artists have been coming to Yenan and our other anti-Japanese base

areas. But it does not necessarily follow that, having come to the base

areas, they have already integrated themselves completely with the

masses of the people here. The two must be completely integrated if we

are to push ahead with our revolutionary work. The purpose of our

meeting today is precisely to ensure that literature and art fit well

into the whole revolutionary machine as a component part, that they

operate as powerful weapons for uniting and educating the people and for

attacking and destroying the enemy, and that they help the people fight

the enemy with one heart and one mind. What are the problems that must

be solved to achieve this objective? I think they are the problems of

the class stand of the writers and artists, their attitude, their

audience, their work and their study.

The

problem of class stand. Our stand is that of the proletariat and of the

masses. For members of the Communist Party, this means keeping to the

stand of the Party, keeping to Party spirit and Party policy. Are there

any of our literary and art workers who are still mistaken or not clear

in their understanding of this problem? I think there are. Many of our

comrades have frequently departed from the correct stand.

The

problem of attitude. From one's stand there follow specific attitudes

towards specific matters. For instance, is one to extol or to expose?

This is a question of attitude. Which attitude is wanted? I would say

both. The question is, whom are you dealing with? There are three kinds

of persons, the enemy, our allies in the united front and our own

people; the last are the masses and their vanguard. We need to adopt a

different attitude towards each of the three. With regard to the enemy,

that is, Japanese imperialism and all the other enemies of the people,

the task of revolutionary writers and artists is to expose their

duplicity and cruelty and at the same time to point out the

inevitability of their defeat, so as to encourage the anti-Japanese army

and people to fight staunchly with one heart and one mind for their

overthrow. With regard to our different allies in the united front, our

attitude should be one of both alliance and criticism, and there should

be different kinds of alliance and different kinds of criticism. We

support them in their resistance to Japan and praise them for any

achievement. But if they are not active in the War of Resistance, we

should criticize them. If anyone opposes the Communist Party and the

people and keeps moving down the path of reaction, we will firmly oppose

him. As for the masses of the people, their toil and their struggle,

their army and their Party, we should certainly praise them. The people,

too, have their shortcomings.

Berkeley Juneteenth Festival, Sunday, June 19, 2016

Dear Friends, Supporters, Entertainers, Vendors and Program Editors:

Regarding the attached media releases, please consider promoting and covering the 29th Annual Berkeley Juneteenth Festival to be held on Sunday, June 19, 2016 from 11am-7pm (Alcatraz @ Adeline), in the city of Berkeley.

2016 Participants: Post on your social sites your performance/vending, "like us" on Facebook: berkeleycajuneteenth, and "share" with your contacts.

Vendor space is still open. Go to www.berkeleyjuneteenth.org and download an application.

Looking forward to a successful event!

Delores Nochi Cooper

Publicity Chair

Berkeley Juneteenth Association, Inc.

Mao on Petty-bourgeois ideas

Among the proletariat many retain petty-bourgeois ideas, while both the peasants and the urban petty bourgeoisie have backward ideas; these are burdens hampering them in their struggle. We should be patient and spend a long time in educating them and helping them to get these loads off their backs and combat their own shortcomings and errors, so that they can advance with great strides. They have remoulded themselves in struggle or are doing so, and our literature and art should depict this process. As long as they do not persist in their errors, we should not dwell on their negative side and consequently make the mistake of ridiculing them or, worse still, of being hostile to them. Our writings should help them to unite, to make progress, to press ahead with one heart and one mind, to discard what is backward and develop what is revolutionary, and should certainly not do the opposite.

The Problem of Audience

The

problem of audience, i.e., the people for whom our works of literature

and art are produced. In the Shensi-Kansu-Ningsia Border Region and the

anti-Japanese base areas of northern and central China, this problem

differs from that in the Kuomintang areas, and differs still more from

that in Shanghai before the War of Resistance. In the Shanghai period,

the audience for works of revolutionary literature and art consisted

mainly of a section of the students, office workers and shop assistants.

After the outbreak of the War of Resistance the audience in the

Kuomintang areas became somewhat wider, but it still consisted mainly of

the same kind of people because the government there prevented the

workers, peasants and soldiers from having access to revolutionary

literature and art. In our base areas the situation is entirely

different. Here the audience for works of literature and art consists of

workers, peasants, soldiers and revolutionary cadres. There are

students in the base areas, too, but they are different from students of

the old type; they are either former or future cadres.

The

cadres of all types, fighters in the army, workers in the factories and

peasants in the villages all want to read books and newspapers once

they become literate, and those who are illiterate want to see plays and

operas, look at drawings and paintings, sing songs and hear music; they

are the audience for our works of literature and art. Take the cadres

alone. Do not think they are few; they far outnumber the readers of any

book published in the Kuomintang areas. There, an edition usually runs

to only 2,000 copies, and even three editions add up to only 6,000; but

as for the cadres in the base areas, in Yenan alone there are more than

10,000 who read books. Many of them, moreover, are tempered

revolutionaries of long standing, who have come from all parts of the

country and will go out to work in different places, so it is very

important to do educational work among them. Our literary and art

workers must do a good job in this respect.

Since

the audience for our literature and art consists of workers, peasants

and soldiers and of their cadres, the problem arises of understanding

them and knowing them well. A great deal of work has to be done in order

to understand them and know them well, to understand and know well all

the different kinds of people and phenomena in the Party and government

organizations, in the villages and factories and in the Eighth Route and

New Fourth Armies. Our writers and artists have their literary and art

work to do, but their primary task is to understand people and know them

well. In this regard, how have matters stood with our writers and

artists? I would say they have been lacking in knowledge and

understanding; they have been like "a hero with no place to display his

prowess". What does lacking in knowledge mean? Not knowing people well.

The writers and artists do not have a good knowledge either of those

whom they describe or of their audience; indeed they may hardly know

them at all. They do not know the workers or peasants or soldiers well,

and do not know the cadres well either. What does lacking in

understanding mean? Not understanding the language, that is, not being

familiar with the rich, lively language of the masses.

Since

many writers and artists stand aloof from the masses and lead empty

lives, naturally they are unfamiliar with the language of the people.

Accordingly, their works are not only insipid in language but often

contain nondescript expressions of their own coining which run counter

to popular usage. Many comrades like to talk about "a mass style". But

what does it really mean? It means that the thoughts and feelings of our

writers and artists should be fused with those of the masses of

workers, peasants and soldiers. To achieve this fusion, they should

conscientiously learn the language of the masses. How can you talk of

literary and artistic creation if you find the very language of the

masses largely incomprehensible? By "a hero with no place to display his

prowess", we mean that your collection of great truths is not

appreciated by the masses. The more you put on the airs of a veteran

before the masses and play the "hero", the more you try to peddle such

stuff to the masses, the less likely they are to accept it. If you want

the masses to understand you, if you want to be one with the masses, you

must make up your mind to undergo a long and even painful process of

tempering. Here I might mention the experience of how my own feelings

changed.

Exiled Black Revolutionaries Mabel Williams, Robert F. Williams (Negroes with Guns) and Chairman Mao Tse-tung in China. When Robert F. Williams was forced into exile, he formed an organization within the USA called

Revolutionary Action Movement or RAM that published the radical Black Arts Movement journal

Soulbook,

edited by Mamadou Lumumba, aka, Kenny Freeman, with contributions by East Coast writers and students

at Oakland's Merritt College, e.g., Ernie Allen, Bobby

Seale, Carol Freeman, Marvin X. East coast writers were Bobb Hamilton,

Amiri Baraka, Askia Toure, James and Grace Boggs, Sonia Sanchez, et al. RAM

also organized the first Black Panther Party in Oakland, the Black

Panther Party of Northern California. The first BPP was dissolved on

pain of death by the Black Panther Party of Self Defense. Max Stanford,

aka Muhammad Ahmad, was RAM USA's leader.

I began life as a student and at school acquired the ways of a student; I then used to feel it undignified to do even a little manual labour, such as carrying my own luggage in the presence of my fellow students, who were incapable of carrying anything, either on their shoulders or in their hands. At that time I felt that intellectuals were the only clean people in the world, while in comparison workers and peasants were dirty. I did not mind wearing the clothes of other intellectuals, believing them clean, but I would not put on clothes belonging to a worker or peasant, believing them dirty. But after I became a revolutionary and lived with workers and peasants and with soldiers of the revolutionary army, I gradually came to know them well, and they gradually came to know me well too. It was then, and only then, that I fundamentally changed the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois feelings implanted in me in the bourgeois schools. I came to feel that compared with the workers and peasants the unremoulded intellectuals were not clean and that, in the last analysis, the workers and peasants were the cleanest people and, even though their hands were soiled and their feet smeared with cow-dung, they were really cleaner than the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois intellectuals. That is what is meant by a change in feelings, a change from one class to another. If our writers and artists who come from the intelligentsia want their works to be well received by the masses, they must change and remould their thinking and their feelings. Without such a change, without such remoulding, they can do nothing well and will be misfits.

The

last problem is study, by which I mean the study of Marxism-Leninism

and of society. Anyone who considers himself a revolutionary Marxist

writer, and especially any writer who is a member of the Communist

Party, must have a knowledge of Marxism-Leninism. At present, however,

some comrades are lacking in the basic concepts of Marxism. For

instance, it is a basic Marxist concept that being determines

consciousness, that the objective realities of class struggle and

national struggle determine our thoughts and feelings. But some of our

comrades turn this upside down and maintain that everything ought to

start from "love". Now as for love, in a class society there can be only

class love; but these comrades are seeking a love transcending classes,

love in the abstract and also freedom in the abstract, truth in the

abstract, human nature in the abstract, etc. This shows that they have

been very deeply influenced by the bourgeoisie. They should thoroughly

rid themselves of this influence and modestly study Marxism-Leninism. It

is right for writers and artists to study literary and artistic

creation, but the science of Marxism-Leninism must be studied by all

revolutionaries, writers and artists not excepted. Writers and artists

should study society, that is to say, should study the various classes

in society, their mutual relations and respective conditions, their

physiognomy and their psychology. Only when we grasp all this clearly

can we have a literature and art that is rich in content and correct in

orientation.

I

am merely raising these problems today by way of introduction; I hope

all of you will express your views on these and other relevant problems.

BH Brilliant Minds Project, Inc

Honoring and Celebrating the Brilliant Minds of the Past, Present and Future

We are excited to announce that the 8th Annual Oakland Juneteenth Celebration is fast approaching! Please join us on Saturday, June 25, 2016 at 925 Brockhurst Street Oakland, CA 94608, between Market Street and San Pablo Avenue for a day for music, free health screens, historical education and family fun. This year’s theme is “Honoring and Celebrating the Brilliant Minds of the Past, Present and Future.” Our event brings together people of all ethnicities and cultures of the Greater Bay Area to celebrate the end of slavery in the United States.

For the last eight years, the Juneteenth Celebration has brought people from all over Oakland together to commemorate this momentous event. Last year over 1,000 people enjoyed the festival that included live music, free health screenings, oral history presentations, free food, quilting, and many other symbolic activities to commemorate our African American heritage. This year we will expand the event to provide even more opportunities for the community to hear from the voices of our ancestors:

9th ANNUAL

West Oakland JUNETEENTH CELEBRATION, June 25, San Pablo and Brockhurst

Honoring and Celebrating the Brilliant Minds of the Past, Present and Future

We are excited to announce that the 8th Annual Oakland Juneteenth Celebration is fast approaching! Please join us on Saturday, June 25, 2016 at 925 Brockhurst Street Oakland, CA 94608, between Market Street and San Pablo Avenue for a day for music, free health screens, historical education and family fun. This year’s theme is “Honoring and Celebrating the Brilliant Minds of the Past, Present and Future.” Our event brings together people of all ethnicities and cultures of the Greater Bay Area to celebrate the end of slavery in the United States.

For the last eight years, the Juneteenth Celebration has brought people from all over Oakland together to commemorate this momentous event. Last year over 1,000 people enjoyed the festival that included live music, free health screenings, oral history presentations, free food, quilting, and many other symbolic activities to commemorate our African American heritage. This year we will expand the event to provide even more opportunities for the community to hear from the voices of our ancestors:

-

Live Blues and Jazz performances

-

Vendors and Community Resource displays and sales

-

Kids Zone

-

Health Zone hosted by Alameda County Public Health Department to provide health

screening & resources -

We invite local organizations and vendors to participate in this wonderful gathering of neighbors. If you would like to secure a vending booth or host a resource table, please complete the attached forms and return them by June 13, 2016. Space is limited and booths will be assigned on a first come, first served basis upon receipt of application, fees, and permits where applicable. Once all documents are received, you will receive confirmation of your space at this year’s festival. If you have any additional questions or need any additional information please contact me at (510)435-1077 or Barbarahoward47@comcast.net. Our hope is that you will seriously consider this invitation and join us as we strive to make a positive difference in our community.

Warm regards.

Barbara Howard

Director of Oakland Juneteenth Festival B.H. Brilliant Minds Project, Inc.

Chairman Mao and W.E.B. DuBois, the greatest intellectual North American Africans produced.

DuBois

became a citizen of Ghana, West Africa. As great as he was, when

Chairman Mao introduced

him before a million people in Tiananmen Square, he turned to Mao and said, "Chairman, thank you

him before a million people in Tiananmen Square, he turned to Mao and said, "Chairman, thank you

for the great introduction but in my country USA, I'm just a nigguh!"

DuBois departed the USA to become a citizen of Ghana, West Africa. Ironically, he criticized Marcus Garvey's Black to Africa Movement. Many North American Africans are leaving the USA for Ghana and other nations in Africa, among them Marvin X's daughter, Muhammida, who now lives and works in Accra, Ghana and has no plans of living again in the USA. She told her dad, "They may not have electricity 24/7 in Ghana but they don't have white supremacy 24/7. Nobody follows me around in the hotels and expensive stores! Dad, you need to get your behind to Ghana!"

DuBois departed the USA to become a citizen of Ghana, West Africa. Ironically, he criticized Marcus Garvey's Black to Africa Movement. Many North American Africans are leaving the USA for Ghana and other nations in Africa, among them Marvin X's daughter, Muhammida, who now lives and works in Accra, Ghana and has no plans of living again in the USA. She told her dad, "They may not have electricity 24/7 in Ghana but they don't have white supremacy 24/7. Nobody follows me around in the hotels and expensive stores! Dad, you need to get your behind to Ghana!"

Left

to right: Muhammida El Muhajir, creator of the Black Arts/Black Power

Babies

Conversation and CEO of Sun in Leo International, now living in Accra,

Ghana, West Africa. Right: Samantha Akwei. She visited Ghana during the

holidays,

connected with Muhammida, daughter of Marvin X and Nisa Ra. Muhammida is

a Howard University graduate, B.S., Microbiology. Samantha is a poet

and Spelman graduate working in Oakland.

muhammida el muhajir, black arts movement baby 2.0

Brand Marketing, Product Manager, and Tech Startup Founder in Brooklyn, New York

Muhammida

El Muhajir is a global brand marketing and media consultant,

entrepreneur and filmmaker with extensive travel/study/work experience

abroad including Europe, Asia, Latin America, The Caribbean, and Africa

(Ghana, Senegal, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa). She has established a

solid reputation and network in her field for her visionary strategies

for innovative brands such as Nike, Diesel, Gatorade, Volkswagen, and

Sony Japan.

As the former Music Marketing Manager at sports powerhouse, Nike, Inc., El Muhajir spearheaded pioneering marketing campaigns and programs with industry heavyweights, Eminem, Outkast, Alicia Keys, Pharrell Williams, and Island Def Jam Records.

Through the creative agency, Sun in Leo, she produced the acclaimed ‘Street Stylez ‘ international fashion tour in Sao Paulo, Tokyo, and Paris as well as the ground breaking documentary, “Hip Hop: the New World Order” exploring the global impact of hip hop establishing El Muhajir as an expert voice on international trends in music, fashion, art, and culture.

She has presented at The United Nations, Oxford University, The Brooklyn Museum, and UC Berkeley and her works have been incorporated into the curriculum at The New School, The University of Sheffield (UK) and Harvard University.

One of El Muhajir's endeavors, frank white, a Brooklyn cafe/gallery space was nominated 'Best New Coffeehouse' by Time Out NY magazine and noted in many global publications for its focus on design and cultural engagement.

El Muhajir pursued a Masters degree in International Relations at The University of Ghana and received a Bachelor of Science in Microbiology with a double minor in Chemistry and Communications from Howard University where she attended on a full athletic scholarship.

To complement her traditional marketing expertise with digital technology, El Muhajir completed a one year Fellowship at the Meltwater Entrepreneurial School of Technology (MEST) Incubator in Accra, providing Business Development to a portfolio of tech start ups from Ghana and Nigeria.

She currently works developing digital marketing strategies for clients in West Africa and will soon launch the beauty product review app, Beauty Radical.

As the former Music Marketing Manager at sports powerhouse, Nike, Inc., El Muhajir spearheaded pioneering marketing campaigns and programs with industry heavyweights, Eminem, Outkast, Alicia Keys, Pharrell Williams, and Island Def Jam Records.

Through the creative agency, Sun in Leo, she produced the acclaimed ‘Street Stylez ‘ international fashion tour in Sao Paulo, Tokyo, and Paris as well as the ground breaking documentary, “Hip Hop: the New World Order” exploring the global impact of hip hop establishing El Muhajir as an expert voice on international trends in music, fashion, art, and culture.

She has presented at The United Nations, Oxford University, The Brooklyn Museum, and UC Berkeley and her works have been incorporated into the curriculum at The New School, The University of Sheffield (UK) and Harvard University.

One of El Muhajir's endeavors, frank white, a Brooklyn cafe/gallery space was nominated 'Best New Coffeehouse' by Time Out NY magazine and noted in many global publications for its focus on design and cultural engagement.

El Muhajir pursued a Masters degree in International Relations at The University of Ghana and received a Bachelor of Science in Microbiology with a double minor in Chemistry and Communications from Howard University where she attended on a full athletic scholarship.

To complement her traditional marketing expertise with digital technology, El Muhajir completed a one year Fellowship at the Meltwater Entrepreneurial School of Technology (MEST) Incubator in Accra, providing Business Development to a portfolio of tech start ups from Ghana and Nigeria.

She currently works developing digital marketing strategies for clients in West Africa and will soon launch the beauty product review app, Beauty Radical.

CONCLUSION

May 23, 1942

Comrades!

Our forum has had three meetings this month. In the pursuit of truth we

have carried on spirited debates in which scores of Party and non-Party

comrades have spoken, laying bare the issues and making them more

concrete. This, I believe, will very much benefit the whole literary and artistic movement.

In

discussing a problem, we should start from reality and not from

definitions. We would be following a wrong method if we first looked up

definitions of literature and art in textbooks and then used them to

determine the guiding principles for the present-day literary and

artistic movement and to judge the different opinions and controversies

that arise today. We are Marxists, and Marxism teaches that in our

approach to a problem we should start from objective facts, not from

abstract definitions, and that we should derive our guiding principles,

policies and measures from an analysis of these facts. We should do the

same in our present discussion of literary and artistic work.

What

are the facts at present? The facts are: the War of Resistance Against

Japan which China has been fighting for five years; the world-wide

anti-fascist war; the vacillations of China's big landlord class and big

bourgeoisie in the War of Resistance and their policy of high-handed

oppression of the people; the revolutionary movement in literature and

art since the May 4th Movement--its great contributions to the

revolution during the last twenty-three years and its many shortcomings;

the anti-Japanese democratic base areas of the Eighth Route and New

Fourth Armies and the integration of large numbers of writers and

artists with these armies and with the workers and peasants in these

areas; the difference in both environment and tasks between the writers

and artists in the base areas and those in the Kuomintang areas; and the

controversial issues concerning literature and art which have arisen in

Yenan and the other anti-Japanese base areas. These are the actual,

undeniable facts in the light of which we have to consider our problems.

What

then is the crux of the matter? In my opinion, it consists

fundamentally of the problems of working for the masses and how to work

for the masses. Unless these two problems are solved, or solved

properly, our writers and artists will be ill-adapted to their

environment and their tasks and will come up against a series of

difficulties from without and within. My concluding remarks will centre

on these two problems and also touch upon some related ones.

I

The first problem is: literature and art for whom?

This

problem was solved long ago by Marxists, especially by Lenin. As far

back as 1905 Lenin pointed out emphatically that our literature and art

should "serve . . . the millions and tens of millions of working

people".[1] For

comrades engaged in literary and artistic work in the anti-Japanese

base areas it might seem that this problem is already solved and needs

no further discussion. Actually, that is not the case. Many comrades

have not found a clear solution. Consequently their sentiments, their

works, their actions and their views on the guiding principles for

literature and art have inevitably been more or less at variance with

the needs of the masses and of the practical struggle.

Of

course, among the numerous men of culture, writers, artists and other

literary and artistic workers engaged in the great struggle for

liberation together with the Communist Party and the Eighth Route and

New Fourth Armies, a few may be careerists who are with us only

temporarily, but the overwhelming majority are working energetically for

the common cause. By relying on these comrades, we have achieved a

great deal in our literature, drama, music and fine arts. Many of these

writers and artists have begun their work since the outbreak of the War

of Resistance; many others did much revolutionary work before the war,

endured many hardships and influenced broad masses of the people by

their activities and works. Why do we say, then, that even among these

comrades there are some who have not reached a clear solution of the

problem of whom literature and art are for? Is it conceivable that there

are still some who maintain that revolutionary literature and art are

not for the masses of the people but for the exploiters and oppressors?

Indeed

literature and art exist which are for the exploiters and oppressors.

Literature and art for the landlord class are feudal literature and art.

Such were the literature and art of the ruling class in China's feudal

era. To this day such literature and art still have considerable

influence in China. Literature and art for the bourgeoisie are bourgeois

literature and art. People like Liang Shih-chiu, [2] whom

Lu Hsun criticized, talk about literature and art as transcending

classes, but in fact they uphold bourgeois literature and art and oppose

proletarian literature and art. Then literature and art exist which

serve the imperialists--for example, the works of Chou Tsojen, Chang

Tzu-ping [3]

and their like--which we call traitor literature and art. With us,

literature and art are for the people, not for any of the above groups.

We have said that China's new culture at the present stage is an

anti-imperialist, anti-feudal culture of the masses of the people under

the leadership of the proletariat. Today, anything that is truly of the

masses must necessarily be led by the proletariat. Whatever is under the

leadership of the bourgeoisie cannot possibly be of the masses.

Naturally, the same applies to the new literature and art which are part

of the new culture. We should take over the rich legacy and the good

traditions in literature and art that have been handed down from past

ages in China and foreign countries, but the aim must still be to serve

the masses of the people. Nor do we refuse to utilize the literary and

artistic forms of the past, but in our hands these old forms, remoulded

and infused with new content, also become something revolutionary in the

service of the people.

Who,

then, are the masses of the people? The broadest sections of the

people, constituting more than 90 per cent of our total population, are

the workers, peasants, soldiers and urban petty bourgeoisie. Therefore,

our literature and art are first for the workers, the class that leads

the revolution. Secondly, they are for the peasants, the most numerous

and most steadfast of our allies in the revolution. Thirdly, they are

for the armed workers and peasants, namely, the Eighth Route and New

Fourth Armies and the other armed units of the people, which are the

main forces of the revolutionary war. Fourthly, they are for the

labouring masses of the urban petty bourgeoisie and for the

petty-bourgeois intellectuals, both of whom are also our allies in the

revolution and capable of long-term co-operation with us. These four

kinds of people constitute the overwhelming majority of the Chinese

nation, the broadest masses of the people.

Our

literature and art should be for the four kinds of people we have

enumerated. To serve them, we must take the class stand of the

proletariat and not that of the petty bourgeoisie. Today, writers who

cling to an individualist, petty-bourgeois stand cannot truly serve the

masses of revolutionary workers, peasants and soldiers. Their interest

is mainly focused on the small number of petty-bourgeois intellectuals.

This is the crucial reason why some of our comrades cannot correctly

solve the problem of "for whom?" In saying this I am not referring to

theory. In theory, or in words, no one in our ranks regards the masses

of workers, peasants and soldiers as less important than the

petty-bourgeois intellectuals. I am referring to practice, to action. In

practice, in action, do they regard petty-bourgeois intellectuals as

more important than workers, peasants and soldiers? I think they do.

**********************************************************

Through the “B.A.B.E. Stop the Violence Campaign”, we

are raising funds to

assist various Bay Area Non-profit organizations who specialize in helping women

and children (victims) of domestic violence and abuse. Statistics have proven

that 1 in every 4 women will experience some kind of physical assault in her

lifetime. It is important to bring this travesty out of the shadows and into the

light. With your assistance, we can help those directly affected; their

families and even their

communities get the

support they need.

**********************************************************

Marvin

X and the Black Arts Movement Poets Choir and Arkestra, featuring

David Murray and Earle Davis, Malcolm X Jazz Festival, 2014, Oakland

photo Adam Turner

Marvin

X is the author of 30 books, including poetry, essays, autobiography,

memoir. He received his A.A., Sociology, Merritt College, 1964; B.A.,

M.A., English, San Francisco State University, 1974-75. He has taught at

Fresno State University, University of

California, Berkeley and San Diego, San Francisco State University,

Mills College, University of Nevada, Reno, Laney College, Merritt

College. He received writing fellowships from Columbia University (via

Harlem Cultural Council) and the National Endowment for the Arts;

planning grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, via the

Nevada Cultural Council. His archives were acquired by the Bancroft

Library, University of California, Berkeley. Most recently, Marvin

helped the City of Oakland create the Black Arts Movement Business

District along the 14th Street corridor, downtown.

Many comrades concern themselves with studying the petty-bourgeois intellectuals and analysing their psychology, and they concentrate on portraying these intellectuals and excusing or defending their shortcomings, instead of guiding the intellectuals to join with them in getting closer to the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers, taking part in the practical struggles of the masses, portraying and educating the masses. Coming from the petty bourgeoisie and being themselves intellectuals, many comrades seek friends only among intellectuals and concentrate on studying and describing them. Such study and description are proper if done from a proletarian position. But that is not what they do, or not what they do fully. They take the petty-bourgeois stand and produce works that are the self-expression of the petty bourgeoisie, as can be seen in quite a number of literary and artistic products. Often they show heartfelt sympathy for intellectuals of petty-bourgeois origin, to the extent of sympathizing with or even praising their shortcomings. On the other hand, these comrades seldom come into contact with the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers, do not understand or study them, do not have intimate friends among them and are not good at portraying them; when they do depict them, the clothes are the clothes of working people but the faces are those of petty-bourgeois intellectuals. In certain respects they are fond of the workers, peasants and soldiers and the cadres stemming from them; but there are times when they do not like them and there are some respects in which they do not like them: they do not like their feelings or their manner or their nascent literature and art (the wall newspapers, murals, folk songs, folk tales, etc.).

At

times they are fond of these things too, but that is when they are

hunting for novelty, for something with which to embellish their own

works, or even for certain backward features. At other times they openly

despise these things and are partial to what belongs to the

petty-bourgeois intellectuals or even to the bourgeoisie. These comrades

have their feet planted on the side of the petty-bourgeois

intellectuals; or, to put it more elegantly, their innermost soul is

still a kingdom of the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia. Thus they have

not yet solved, or not yet clearly solved, the problem of "for whom?"

This applies not only to newcomers to Yenan; even among comrades who

have been to the front and worked for a number of years in our base

areas and in the Eighth Route and New Fourth Armies, many have not

completely solved this problem. It requires a long period of time, at

least eight or ten years, to solve it thoroughly. But however long it

takes, solve it we must and solve it unequivocally and thoroughly. Our

literary and art workers must accomplish this task and shift their

stand; they must gradually move their feet over to the side of the

workers, peasants and soldiers, to the side of the proletariat, through

the process of going into their very midst and into the thick of

practical struggles and through the process of studying Marxism and

society. Only in this way can we have a literature and art that are

truly for the workers, peasants and soldiers, a truly proletarian

literature and art.

This

question of "for whom?" is fundamental; it is a question of principle.

The controversies and divergences, the opposition and disunity arising

among some comrades in the past were not on this fundamental question of

principle but on secondary questions, or even on issues involving no

principle. On this question of principle, however, there has been hardly

any divergence between the two contending sides and they have shown

almost complete agreement; to some extent, both tend to look down upon

the workers, peasants and soldiers and divorce themselves from the

masses. I say "to some extent" because, generally speaking, these

comrades do not look down upon the workers, peasants and soldiers or

divorce themselves from the masses in the same way as the Kuomintang

does. Nevertheless, the tendency is there. Unless this fundamental

problem is solved, many other problems will not be easy to solve. Take,

for instance, the sectarianism in literary and art circles. This too is a

question of principle, but sectarianism can only be eradicated by

putting forward and faithfully applying the slogans, "For the workers

and peasants!", "For the Eighth Route and New Fourth Armies!" and "Go

among the masses!" Otherwise the problem of sectarianism can never be

solved. Lu Hsun once said:

A

common aim is the prerequisite for a united front.... The fact that our

front is not united shows that we have not been able to unify our aims,

and that some people are working only for small groups or indeed only

for themselves. If we all aim at serving the masses of workers and

peasants, our front will of course be united.[4]

The

problem existed then in Shanghai; now it exists in Chungking too. In

such places the problem can hardly be solved thoroughly, because the

rulers oppress the revolutionary writers and artists and deny them the

freedom to go out among the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers.

Here with us the situation is entirely different. We encourage

revolutionary writers and artists to be active in forming intimate

contacts with the workers, peasants and soldiers, giving them complete

freedom to go among the masses and to create a genuinely revolutionary

literature and art. Therefore, here among us the problem is nearing

solution. But nearing solution is not the same as a complete and

thorough solution. We must study Marxism and study society, as we have

been saying, precisely in order to achieve a complete and thorough

solution. By Marxism we mean living Marxism which plays an effective

role in the life and struggle of the masses, not Marxism in words. With

Marxism in words transformed into Marxism in real life, there will be no

more sectarianism. Not only will the problem of sectarianism be solved,

but many other problems as well.

II

Having

settled the problem of whom to serve, we come to the next problem, how

to serve. To put it in the words of some of our comrades: should we

devote ourselves to raising standards, or should we devote ourselves to

popularization?

In

the past, some comrades, to a certain or even a serious extent,

belittled and neglected popularization and laid undue stress on raising

standards. Stress should be laid on raising standards, but to do so

one-sidedly and exclusively, to do so excessively, is a mistake. The

lack of a clear solution to the problem of "for whom?", which I referred

to earlier, also manifests itself in this connection. As these comrades

are not clear on the problem of "for whom?", they have no correct

criteria for the "raising of standards" and the "popularization" they

speak of, and are naturally still less able to find the correct

relationship between the two. Since our literature and art are basically

for the workers, peasants and soldiers, "popularization" means to

popularize among the workers, peasants and soldiers, and "raising

standards" means to advance from their present level.

What

should we popularize among them? Popularize what is needed and can be

readily accepted by the feudal landlord class? Popularize what is needed

and can be readily accepted by the bourgeoisie? Popularize what is

needed and can be readily accepted by the petty-bourgeois intellectuals?

No, none of these will do. We must popularize only what is needed and

can be readily accepted by the workers, peasants and soldiers

themselves. Consequently, prior to the task of educating the workers,

peasants and soldiers, there is the task of learning from them. This is

even more true of raising standards. There must be a basis from which to

raise. Take a bucket of water, for instance; where is it to be raised

from if not from the ground? From mid-air? From what basis, then, are

literature and art to be raised? From the basis of the feudal classes?

From the basis of the bourgeoisie? From the basis of the petty-bourgeois

intellectuals? No, not from any of these; only from the basis of the

masses of workers, peasants and soldiers. Nor does this mean raising the

workers, peasants and soldiers to the "heights" of the feudal classes,

the bourgeoisie or the petty-bourgeois intellectuals; it means raising

the level of literature and art in the direction in which the workers,

peasants and soldiers are themselves advancing, in the direction in

which the proletariat is advancing. Here again the task of learning from

the workers, peasants and soldiers comes in. Only by starting from the

workers, peasants and soldiers can we have a correct understanding of

popularization and of the raising of standards and find the proper

relationship between the two.

In

the last analysis, what is the source of all literature and art? Works

of literature and art, as ideological forms, are products of the

reflection in the human brain of the life of a given society.

Revolutionary literature and art are the products of the reflection of

the life of the people in the brains of revolutionary writers and

artists. The life of the people is always a mine of the raw materials

for literature and art, materials in their natural form, materials that

are crude, but most vital, rich and fundamental; they make all

literature and art seem pallid by comparison; they provide literature

and art with an inexhaustible source, their only source. They are the

only source, for there can be no other. Some may ask, is there not

another source in books, in the literature and art of ancient times and

of foreign countries? In fact, the literary and artistic works of the

past are not a source but a stream; they were created by our

predecessors and the foreigners out of the literary and artistic raw

materials they found in the life of the people of their time and place.

We must take over all the fine things in our literary and artistic

heritage, critically assimilate whatever is beneficial, and use them as

examples when we create works out of the literary and artistic raw

materials in the life of the people of our own time and place. It makes a

difference whether or not we have such examples, the difference between

crudeness and refinement, between roughness and polish, between a low

and a high level, and between slower and faster work. Therefore, we must

on no account reject the legacies of the ancients and the foreigners or

refuse to learn from them, even though they are the works of the feudal

or bourgeois classes. But taking over legacies and using them as

examples must never replace our own creative work; nothing can do that.

Uncritical transplantation or copying from the ancients and the

foreigners is the most sterile and harmful dogmatism in literature and

art.

China's

revolutionary writers and artists, writers and artists of promise, must

go among the masses; they must for a long period of time unreservedly

and whole-heartedly go among the masses of workers, peasants and

soldiers, go into the heat of the struggle, go to the only source, the

broadest and richest source, in order to observe, experience, study and

analyse all the different kinds of people, all the classes, all the

masses, all the vivid patterns of life and struggle, all the raw

materials of literature and art. Only then can they proceed to creative

work. Otherwise, you will have nothing to work with and you will be

nothing but a phoney writer or artist, the kind that Lu Hsun in his will

so earnestly cautioned his son never to become.[5]

Although

man's social life is the only source of literature and art and is

incomparably livelier and richer in content, the people are not

satisfied with life alone and demand literature and art as well. Why?

Because, while both are beautiful, life as reflected in works of

literature and art can and ought to be on a higher plane, more intense,

more concentrated, more typical, nearer the ideal, and therefore more

universal than actual everyday life. Revolutionary literature and art

should create a variety of characters out of real life and help the

masses to propel history forward. For example, there is suffering from

hunger, cold and oppression on the one hand, and exploitation and

oppression of man by man on the other. These facts exist everywhere and

people look upon them as commonplace. Writers and artists concentrate

such everyday phenomena, typify the contradictions and struggles within

them and produce works which awaken the masses, fire them with

enthusiasm and impel them to unite and struggle to transform their

environment. Without such literature and art, this task could not be

fulfilled, or at least not so effectively and speedily.

What

is meant by popularizing and by raising standards in works of

literature and art? What is the relationship between these two tasks?

Popular works are simpler and plainer, and therefore more readily

accepted by the broad masses of the people today. Works of a higher

quality, being more polished, are more difficult to produce and in

general do not circulate so easily and quickly among the masses at

present. The problem facing the workers, peasants and soldiers is this:

they are now engaged in a bitter and bloody struggle with the enemy but

are illiterate and uneducated as a result of long years of rule by the

feudal and bourgeois classes, and therefore they are eagerly demanding

enlightenment, education and works of literature and art which meet

their urgent needs and which are easy to absorb, in order to heighten

their enthusiasm in struggle and confidence in victory, strengthen their

unity and fight the enemy with one heart and one mind. For them the