Walking into the Bilbao Guggenheim's galleries to see their Basquiat retrospective, you can hear Martin Luther King's I Have A Dream speech booming out of the speakers. By the exhibition's end Charlie Parker's Now's The Time has replaced it as the soundtrack. Together they sum up two very different aspects of Basquiat; part Harlem Renaissance, part child of the civil rights era. His art turned these influences into something strikingly of its time, and as the exhibitions reveals, reverberates still today.

It's hard sometimes to see Basquiat the artist from the baggage of Basquiat the cultural icon. It's easy to overlook just how talented he was, his skill with composition and colour, density and structure; because Basquiat's life clouds his paintings. As Glenn O'Brien, writer of the Basquiat-starring Downtown 81, says, "Basquiat's got fans like Bob Marley's got fans." So it's odd to consider that he's not had a major museum retrospective in Europe until now, seeing as he's one of the few artists whose cultural place transcends beyond the worlds of art. He should be selling out blockbuster exhibitions at the Tate and Pompidou, but has been relegated to small, niche institutions outside of Europe's major public galleries.

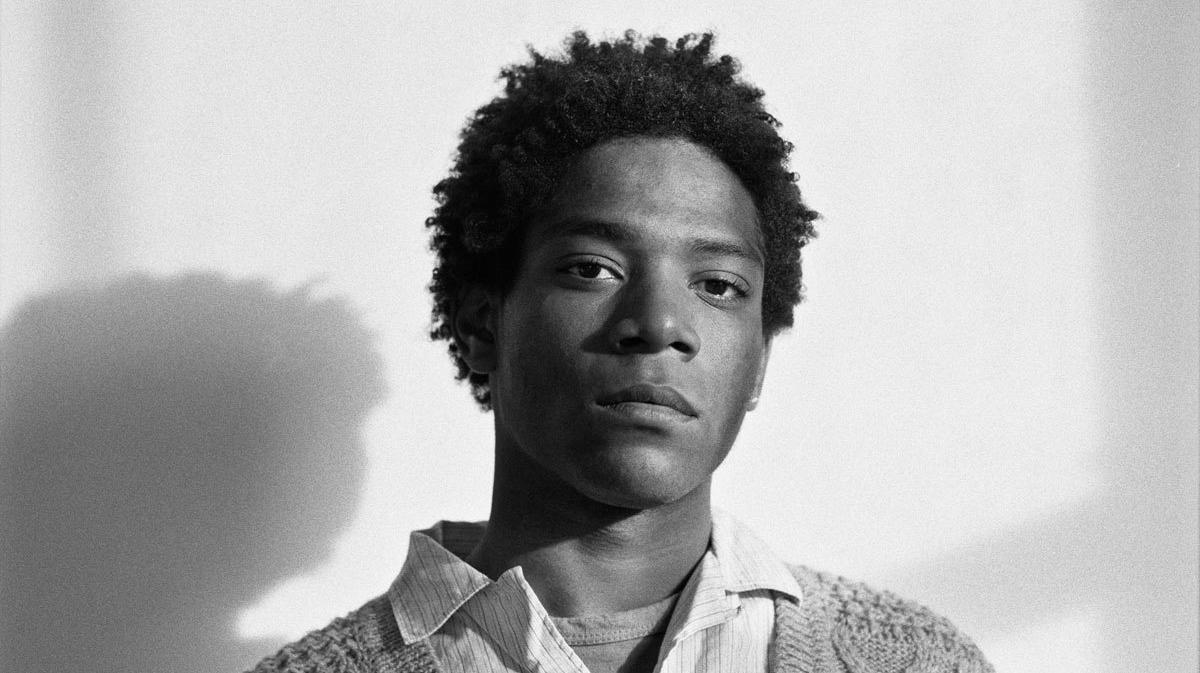

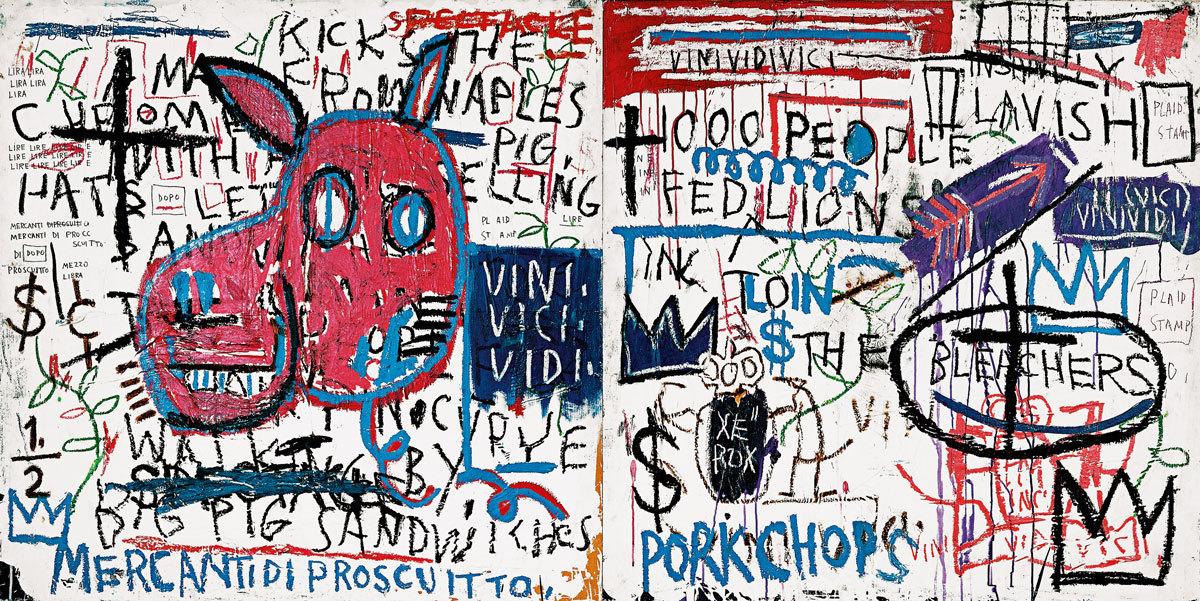

Jean-Michel Basquiat Loin, 1982 © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

When he died, aged just 27, of a heroin overdose, he left a legacy of over 1000 paintings and 3000 drawings. A life's work compiled in just 12 years. He'd gone from the streets to the elite of the art world, and most importantly, took the streets with him.

Basquiat's place in the world has always existed uneasily between extremes. He was a downtown punk and an uptown b-boy; he easily slipped between high culture and low culture, between Madonna and Andy Warhol. He came from the counter-cultural immediacy and language of graffiti, but his work tackles the serious legacy of Cy Twombly, Pablo Picasso and Francis Bacon. He's invoked by Jay Z as a status symbol and by Killer Mike as a social campaigner. He listened to Ravel's Bolero whilst painting, relaxed to Charlie Parker and Miles Davis, and performed in an experimental punk band called Gray. In a minimalist age he created incredibly complex work yet was still seen as a savant; as art's primal, wild man. The immediacy of his image making defies the complex arrangements that go into them, their casual beauty a cipher for an incredibly detailed visual language that he created, and he made these complex and difficult things look easy. He was the First Black Art Star, took black expression into the New York's white gallery scene, and became a genuine celebrity.

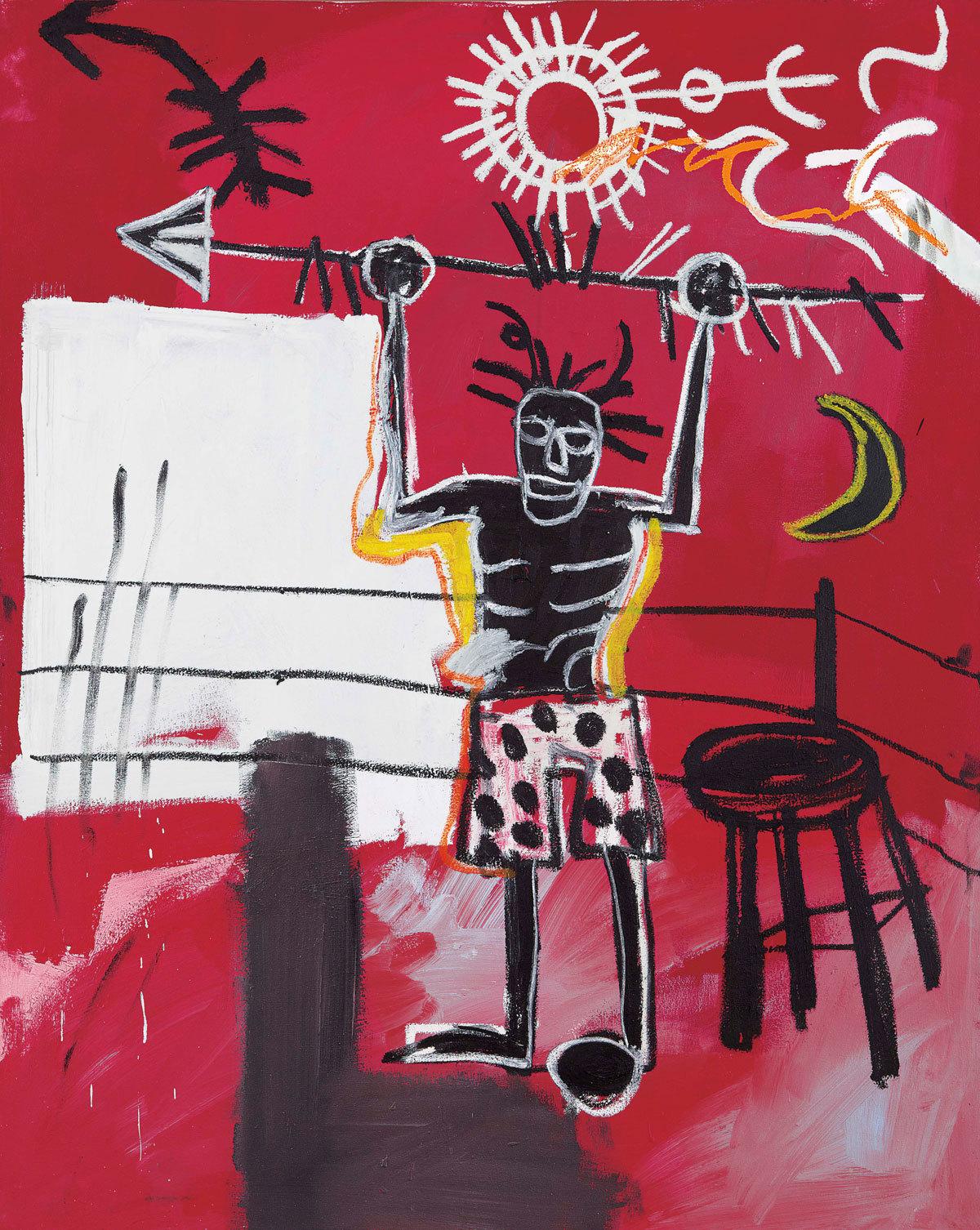

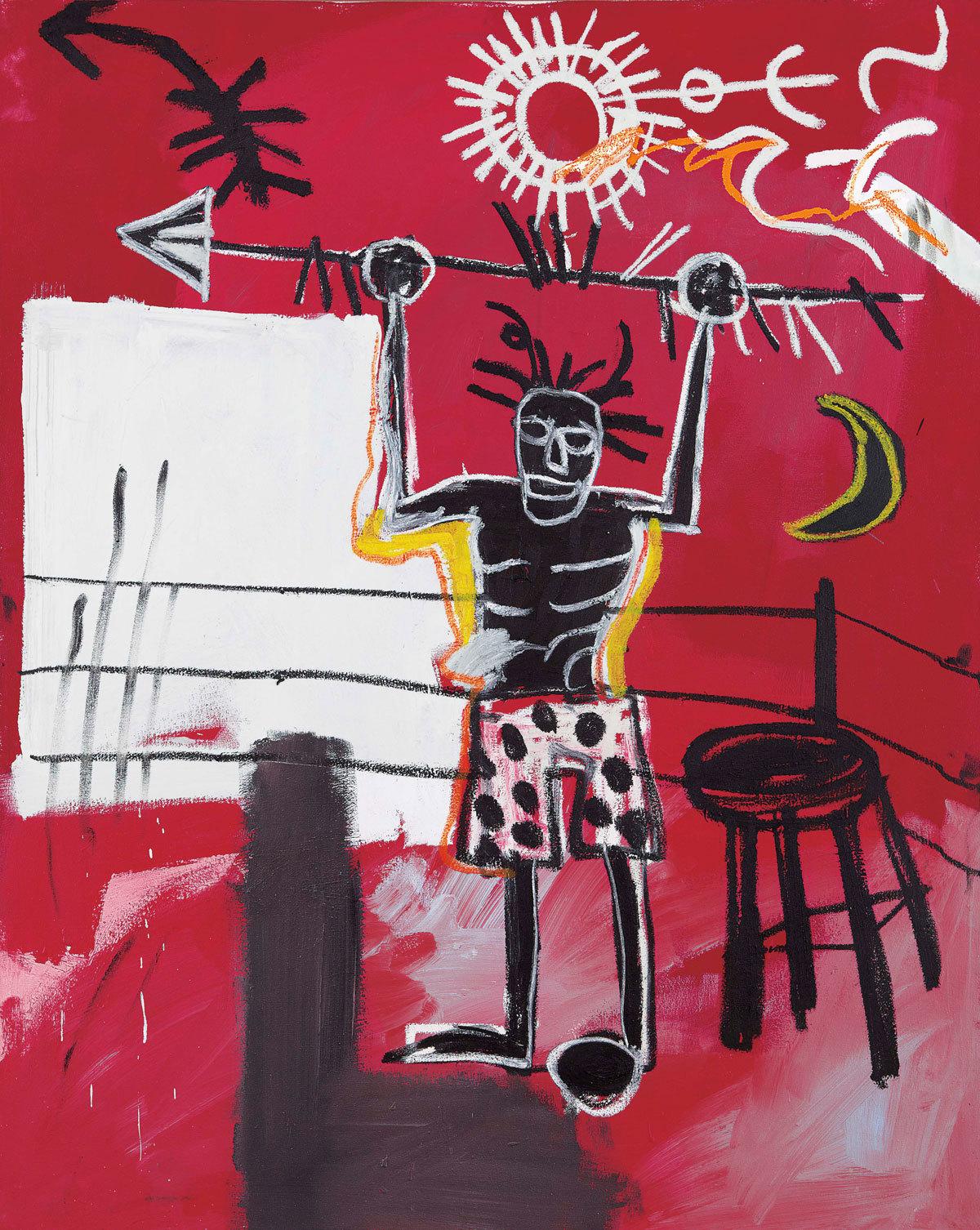

Jean Michel Basquiat The Ring, 1981. Private Collection, Courtesy Acquavella Galleries © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

"So what do we do," the poet Christian Campbell asks "with the cult mythologies about Basquiat, in which criticism on his art amounts to a TMZ report (Who did he fuck? How did he die? What was he on? How was his hair?)" The Guggenheim show's answer, refreshingly, is to ignore it and focus on the art.

The early paintings, made largely on reclaimed materials, pieces of boards, abandoned doors, bear the influences of Basquiat's time on the streets as a graffiti artist, his childhood dream of being a cartoonist, and his obsession with art history.

He also found black heroes missing in art, so figured them into his own work, and so turned modern black life into art. He saw the nobility and tradition of black life and culture as absent and venerated it. Early paintings like Famous Negro Athletes, that feature a scratched back face, a baseball, his signature crown; or King of Baseball, a blue figure, crown, and baseball. These are simple and forceful images, using single lines and few colours, and that minimalism reinforces their political point.

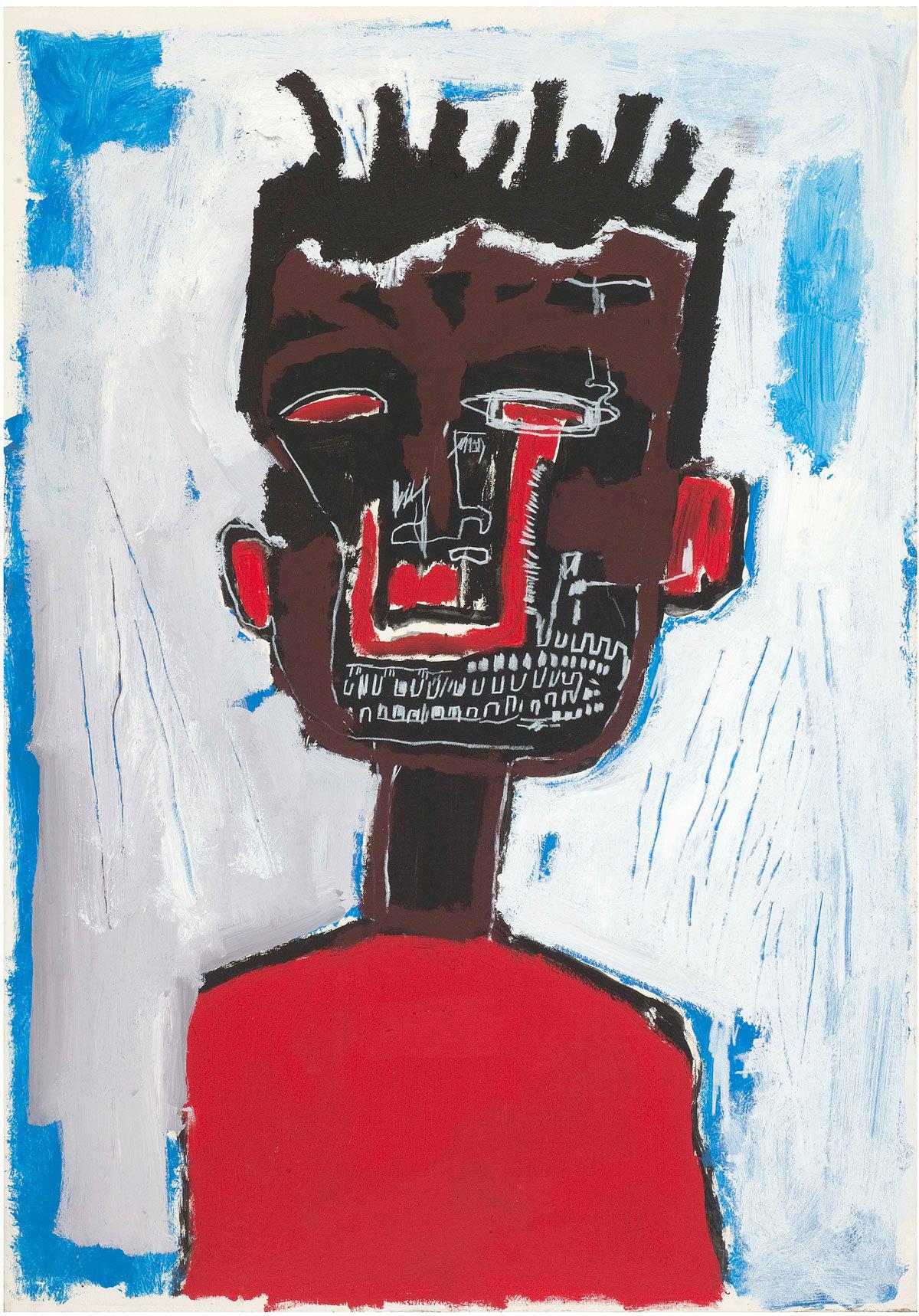

Jean Michel Basquiat Self-Portrait, 1984. Yoav Harlap Collection © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Soon though, his paintings were becoming incredibly complex as he developed his unique visual language. His recurring motifs of black heads, crowns, copyright symbols, baseball players, boxers, text, text scratched out, bodies and the fascination with disembodiment; these motifs spread across his entire work, they crop up again and again, forming a visual link between his works.

In sportspeople, the boxers and baseball players, he saw African American heroes, he saw struggle, resistance, victory and strength. He often talked of having a boxing match with Julian Schnabel. His exhibition of collaborative paintings with Andy Warhol featuring a poster of both of them wearing boxing gloves. It was art as competition, and Basquiat sought to prove himself, as a black man in a white world.

Seeing so many of Basquiat's painting in once place, it becomes clearer and clearer that Basquiat's work's major theme is an unending questioning of America's racial politics and social hypocrisies. A critique of a world where he could sell work to collectors for incredible amounts of money and yet not be able to get a taxi home; where his friend and fellow graffiti writer, Michael Stewart, could be arrested and beaten to death by police; by his place as a lauded black artist showing his paintings on white walls, to white people, and by the way people belittled him, saw him as a novelty and treated him as primitive.

Jean-Michel Basquiat Man from Naples, 1982. Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

His painting, Defacement, was a memorial to the his friend Michael Stewart, features two cartoonish, brightly coloured police officers, armed with batons, beating a black silhouette, under the word defacement. Who's being vandalised, who's defaced? The subway car that Michael Stewart was painting when the police attacked him? Or Michael himself. Basquiat paints Michael's body as a silhouette because it's not just a one off, not just Michael, it's any number of black men targeted by police, and it's not gone away.

Michael's death was a watershed moment for Basquiat and his political consciousness. The works up until that point had been content to simply place the black body within art's history, and reclaim it as a form of representation. After his death, they become more implicitly political, less cartoonish, and much angrier. Irony Of Negro Policeman, for example, is a grotesque caricature of the hypocrisy of oppressor joining the oppressed, his face a mask, his body caged in with lines of paint, daubed with the word 'pawn' in the corner.

When Basquiat started to work and become friends with Andy Warhol, in 83/84, he was himself seen as the pawn, Andy's pet, used to keep Andy relevant as his critical acclaim flagged. But Basquiat managed to draw Andy back to painting, in a series of collaborative works exhibited by Tony Shafrazi in 85, as well as a series derived from the The Last Supper, exhibited in Milan. The critics hated them, described Basquiat as an "art world mascot" and an "all too willing accessory"in the New York Times. They fell out, and after Andy's death, Basquiat became inconsolable, and turned to heroin in greater quantities.

Jean Michel Basquiat. Irony of a Negro Policeman, 1981. Private Collection © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

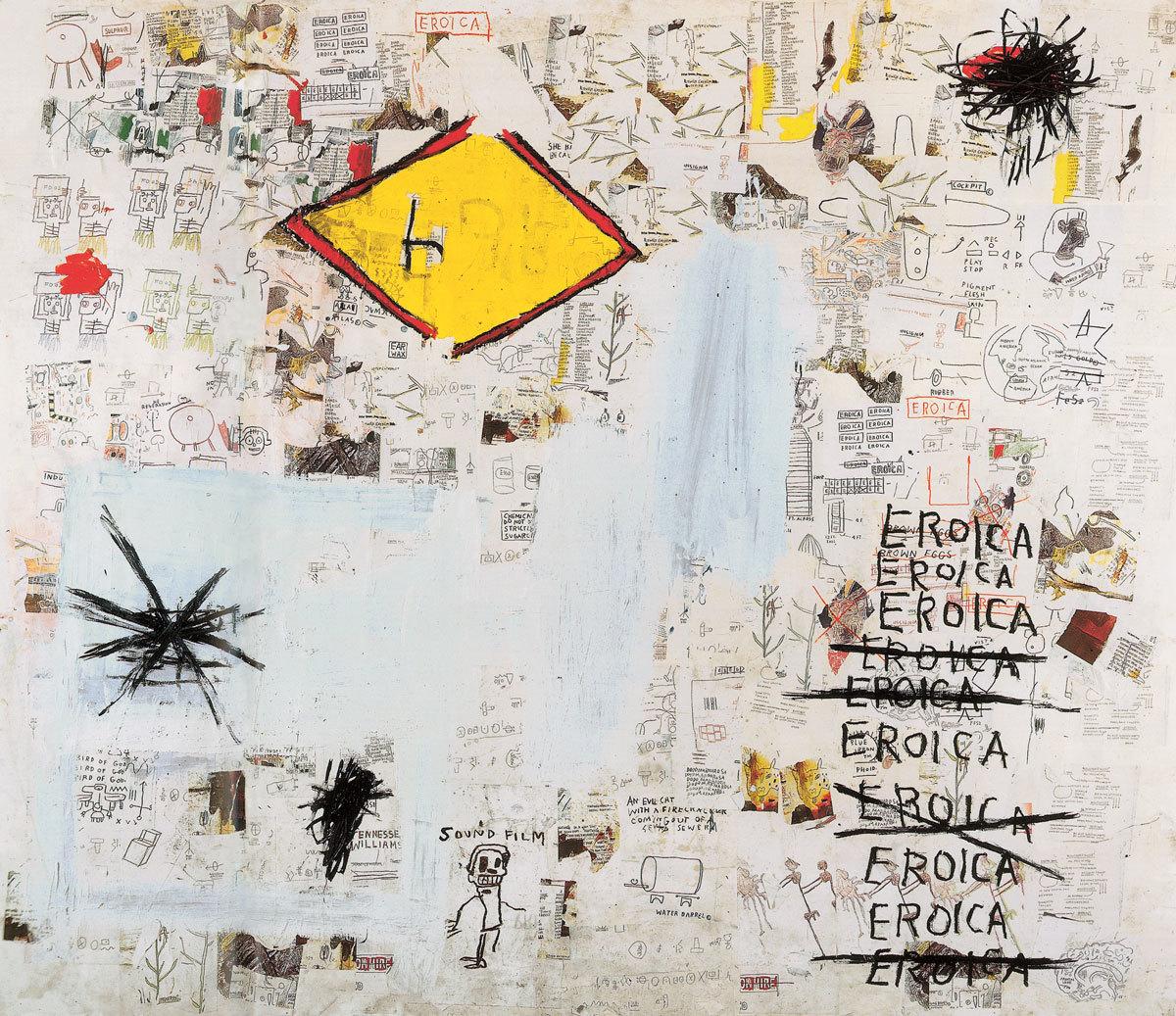

His final works, exhibited for one night only at Baghoomian's gallery at the Cable Building in SoHo, New York, in 1988, just six months before death, show t=his grief, his work is stripped back, stripped of colour, pulsing with the intensity of language. He had become obsessed with listening to Beethoven's Eroica, and specifically, for differences between different versions and interpretations of the symphony. It could act as a metaphor for Basquiat's work as a whole, this revision, sampling, and language of symbols, that runs through his work.

The show is titled Now's The Time, a reference to Charlie Parker, but more obliquely, to Basquiat himself. Now's the time to revisit his work, to give him the museum retrospective his work deserves, but also because it's still the time to evaluate racism and stereotyping, by seeing it again through Basquiat's eyes, it's clear how little has changed in the last 27 years. How many Michael Stewart's have their been this year alone?

Jean-Michel Basquiat Eroica, 1987. Private Collection © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

But also, what Basquiat's career makes clear is how few black artists there've been since, how white the art world remains, and how patronising its attitudes can be. Basquiat might've painted black heroes into art, but he remains one of a few black heroes to make it and prove that black art matters.