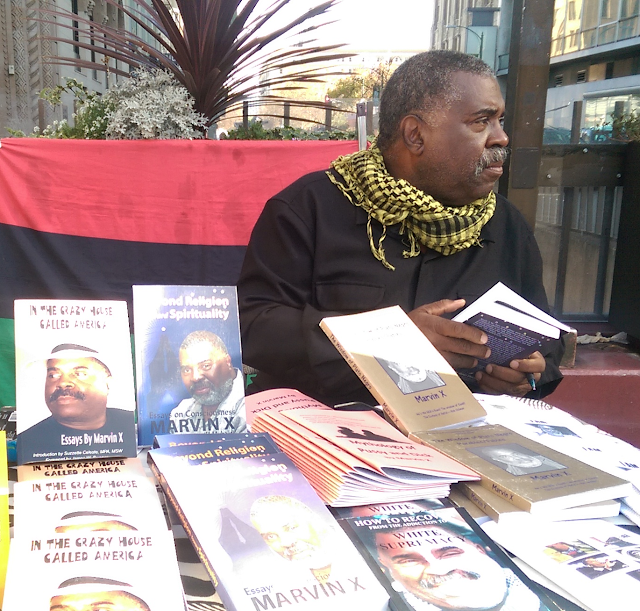

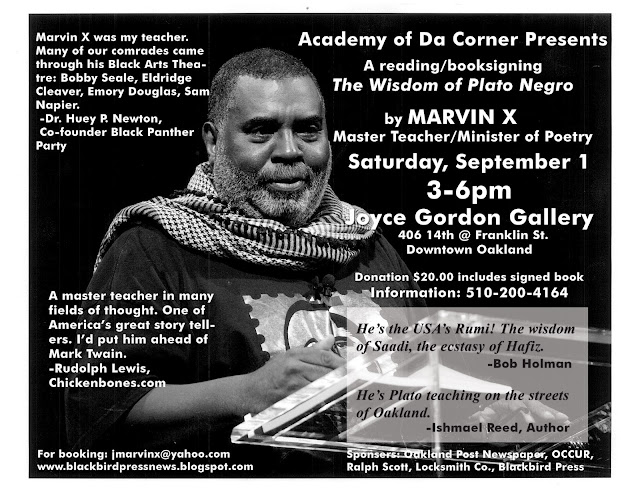

I've been listening to

Wish I, a CD of

an interview of Marvin X on KPOO-Radio in San Francisco. Though

I been checking out Marvin for a season I never been with him in

the flesh and never heard his voice except on the page, and in

cyber-communications. And from reports by Kalamu ya Salaam. The

Wish

I CD affirmed how I imagined him and how I tried to

characterize him in my review of his book of poetry,

Land of My Daughters.

Funny, outrageous, challenging Marvin X is on

the same tier as Amiri Baraka and Kalamu ya Salaam in putting on

an entertaining program. For in "Why I Love

Lesbians," Marvin says, "In their hatred is

drama / I love drama." Marvin's first love is theater; he

is poet and shaman, skilled in manipulating the passions

like the preacher in the pulpit, or the Harlem soapbox

orator, or the barbershop orators found throughout the black

community. In his Wish I Could Tell You the Truth--Essays,

Marvin X has created a book that mirrors the orature in bull

sessions, ubiquitous in black speech and poetry, in the

barbershop.

That is, Malcolm X ain't got nothing on Marvin X. Still

Marvin has been ignored and silenced like Malcolm would be

ignored and silenced if he had lived on into the Now. Marvin's one

of the most extraordinary, exciting black intellectuals living

today--writing, publishing, performing with Sun Ra musicians,

reciting, filming, he's ever engaging, challenging the

respectable and the comfortable. He like Malcolm dares to say

things, fearlessly, in the open (in earshot of the white man)

that so many Negroes feel and think and speak on the corner, in

the barbershops and urban streets of black America.

Discourse by exaggeration and humor has its place in serious

intellectual enquiry. Everybody don't have to wear the nerdy

mask and inky cloak and speak in the autocratic tones of

academia. Marvin's dramatic style and political approach could

not be tolerated at the University since Ronald Reagan forced

him out of the California university system, which signaled the

castration of black studies at white universities.

In short, Wish I Could Tell You the Truth is

one of the most daring, innovative, entertaining group of

"essays" I ever had yet to read. In a true sense this

book is a literary replication of the barbershop experience. The

street rap. Yet much more sophisticated, informed, daring,

philosophical. And it is sheer arrogance and snootiness that he

has been ignored or overlooked by PBS, CNN, and FOX. And by

black literary societies and colleges. Because his thinking is dangerous, and

his simple courage is infectious. And anybody who's heard him

know that Chris Rock and Amiri Baraka ain't got nothing on

Marvin, once he gets to improvising. Marvin is a truth teller,

and just as funky as James Brown.

Wish I Could Tell You the Truth is,

too, an intellectual and philosophical autobiography. Boswell

has nothing on this journalistic foray, that sweeps the

planet in its thinking. Marvin is a storyteller. Like Abby

Lincoln, Marvin's voice matches the story he tells. He ain't no

Cornel West. With Marvin you cannot separate the story from the

voice, one reinforces the other. Though everyday speech is in

Marvin's writing, his writing is artistic writing and different

from his oral performances. Marvin is no linear thinker and so

you have to take him in in the all in all, between the covers, you

got to read him fully to appreciate truly what he has achieved

as an artist and as a man.

The tone of Wish I Could Tell You the Truth

is established in a forty-page autobiographical note beginning

with his birth during an age of war, the impact of broken family

life, youthful love, exposés, going on to his academic career, antiwar

activism, criminal on the run, hustler, civic reformer, and

revolutionary. This autobiographical section is primarily

episodic and expressionistic rather than linear and analytical.

It is Marvin's expertise as storyteller that carries us forward

for his views are often surprising and shocking. Marvin don't

pull no punches when lives are involved.

"Negroes see me and they get on a

skateboard," Marvin observes. "I don't have no

money, I ain't got no bank account, I ain't got no job, and I

ain't had no job in twenty five years, you understand, I

don't have no power but the word, and Negroes run from

me, scare to death, they scared, Mama . . . but they ain't scared of

doing whatever the white man tells him. Going to Iraq, dying like

flies . . . won't die for a purpose. . . . dying on the streets

of America. . . . for no purpose, at all . . . they learn all

this from the white man, really. Because that's how they think.

Bush think there ain't no consequence to his actions. . . Bush always needs another

cowboy . . . but he don't understand . . . the Indians are

coming . . . THE INDIANS ARE COMING . . . they coming for you . . . the

Ancestor Spirits of the Black Man and Woman are coming for you,

Mr. White Man, unless you clean up. . . . you understand."

Now this kind of speech scares Black Academia

in the company of their white colleagues. And the white

professional does not want to endure his female colleagues

squeamish in their chairs because of Marvin's voice. But Marvin is a radical advocate of

free speech, "Don't sell me no sheetrock, for my pipe. . .

. Give me some love, give me some truth. It does not matter

whether you black or white . . . the weapon of today is

consciousness, not color . . . we been trained to be warriors .

. . God was training us for war . . . but they [we] don't have

the right word, the right directions . . . turning them into

constitutional slaves."

Well this kind of nationalist speech would

make a

Martin Kilsonsquirm. There's no place in the academy and black

studies programs for nationalists like a Marvin X or an Amiri

Baraka or a Kalamu ya Salaam. Three of the most extraordinary

men (writers, artists) of our time alienated, separated, barred

from the Academy, and the "accepted" (the

"pragmatic activists") embarrassed by their presence and

speech.

In his response to Reverend Eugene Rivers'

"Beyond

the Nationalism of Fools: Toward An Agenda for Black

Intellectuals" (Boston Review), Kilson argued we don't need "a

new-mode Black nationalist discourse issue . . . . For me, all

variants of Black nationalist modalities have spent-their-load,

as it were, whether here in US, in the Caribbean, or in the many

African states where it is fully bankrupt." So Marvin has

nothing a Kilson can respect, unworthy of his intellectual

attention or recommendation.

Marvin

and Baraka have "spent their load"!!! Is that the real

deal? Or just the Academic Black Ball. But this kind of autocracy

within black political discourse and acts and educational arenas

should have been dispensed with yesterday. Here's a matter in

need of serious consideration. If the Du Bois Chair at Harvard

is going to be the Chair for Black Humanities and the

political, social, and cultural arbiter of Black Life and

Culture, shouldn't we black folks have something to say who sits

in the Chair?

Baraka

had more books, more scholarship than Skip Gates, more

organizational skills, he was more representative of the sentiments of

black youth and Du Bois, an activist scholar, par excellence.

But we didn't have a hand in it, we folk, because white money is more

persuasive, than dedication and sacrifice, and even community shaming. If

we were truly a nation we could by vote choose our

representatives and leaders. We wouldn't have to wait for good

white people to choose them. Let's vote for our Idol.

So

Marvin writes: "The activist scholars were long ago removed

from academia as a threat to Western scholarship and community

liberation. Safe, qualified negroes were brought in who would

control the natives and have them chasing rocks in Egypt rather

than stopping gunshots in the hood by providing alternative

consciousness. . . . Black studies was not about degrees, but

the liberation of a people . . . . the community would be better

served giving consciousness to dry bones in the hood."

But

Strong Men keep on pushing, despite isolation, alienation, and

banishment. There ain't no stopping Strong Men, says Sterling

Brown. And Marvin is a nationalist with a global consciousness.

But our primary "mission is self and community development,

not esoteric journeys to the Motherland to discover much to his

dismay and utter disappointment that he is not an African but a

pitiful American mutation, a mongrel, in short, a white man in

black face, a disconnected descendant, even worse than ET

because he can't call home even when he gets there."

But

it is "even more important that he makes peace with the

trees and swamps and bayous of Mississippi, Alabama and

Louisiana, then perhaps the ancestors in Africa will accept him

and assuage his mind . . . better . . . connect with the ghetto

blacks he . . . earnestly desires to escape." We are schizophrenic

(you know, Du Bois' "double consciousness"). Negroes

"got ten different personalities . . . negroes know

how to act. . . Tom was a killer, he

had murder in his heart." So for the dope gangs, we

need to "make peace with them, teach them to make peace

with themselves." But we also have too many black

celebrities, like Crouch, Cosby, and West, "cultural police

for the black bourgeoise," destructively "Beyond the

Ignorance Zone."

So, you see, Marvin is refreshing. He's a

Liberator. He has freed up contemporary black public speech,

primarily controlled by the hip hop industry, Hollywood, the

communication industry, and educational factories like Harvard

and black public schools. He's like no Muslim you have heard

speak. And this is odd for the usual impulse is to think of

Muslims as limiting speech and especially the speech of women.

For he knows the "light don't come on if you don't turn the

switch. . . . Flip the switch on, dummy . . . you got to put on the

armor of God and you can walk through the valley of shadow and

death. . . . I had the armor of God on me when I was

out there, when I was out there in the projects, on crack."

War, religion, and cultural ethics are the

steak of Marvin's extended discussion. Wish I Could Tell You

the Truth is thus cultural criticism at its best. "In

the Name of Love," Marvin explains, "Love ain't love

if it cuts too deep." For many Marvin probably cuts

"too deep." It's a book that would frighten a Tavis

Smiley or a Jesse Jackson or a Skip Gates. Though he says he's a

Muslim, on reading Marvin you can only guess he is a Muslim. He

don't pray five times a day and he don't ascribe to some of

the cultural practices of some Muslims and thus he has made a

call for a "Radical

Spirituality."

The slave religion cultivated by black

mega-preachers and Saudi-supported Islam are better understood

as a "religion box." Marvin continues, "But we

know the people have been hoodwinked and bamboozled, therefore

it is the mission of the truly spiritually conscious to step to

the front of the line and represent, not hide in the closet and

let the masquerade continue." Marvin is wary of religious

institutions that exist for the priests primarily. "We have

been told to seek ye first the kingdom of heaven and all things,

yea, even political and economic things will be added unto

ye."

Marvin is against imperialist wars, e.g. Iraq

and Haiti. He was a Vietnam-era anti-war activist on the run,

from Canada to Central America. And he takes position on Israel

that no black academic would dare take, no black elected

official would allow pass through his lips. "Israel is the

number one problem in the Middle East. Israel is no less a

fascist, nazi, apartheid state backed with the money and

armaments of America. Israel is the only threat to peace in the

Middle East."

Whether Israel is the "only threat"

my political sympathies do not extend so far. What's troubling

is Israel is beyond criticism, if you want to win public office

in America. And our 800 public black officials and academicians

know how their bread is buttered. And as it used to be with our

black mayors, there is no full criticism, but rather a mumbling,

hypocritical silence. Nationalism is okay for the Jew, but not

the American Negro, for they ain't got no guns and capital, and

certainly, thank God, they ain't nuclear.

So in the spirit of Marvin I'm gonna call on

and thank God, Allah, Jesus, Jah, Jehovah, Buddha, Karl Marx,

and Lenin, and call on the Ancestors to bless you with a copy

of Wish I Could Tell You the Truth. Don't run from

Marvin, give him an ear. The brother got truths you need to hear, that will

clean us up. Liberate the captive. Build a new black world, real

free zones. And he's got some lies, too, but it's all good.

Contrary to Kilson's view, life is still in black nationalism. For

Marvin Black is White and White is Black. He ain't fearing being fired, he says what he wants to say.

. . . Praise God in the name of Love.

Note: Wish I Could Tell You The Truth is out of print.

*

* * * *

Wish I Could Tell You the Truth

Essays by Marvin X

Contents

|

|

|

|

| Chapter One: Tale of an Angry Old Man |

12

|

|

|

| Chapter Two:

Manifesto of The University of Poetry |

52

|

|

|

| Chapter Three:

Toward A Radical Spirituality

|

73

|

| In Search of my Soul Sister |

75

|

| Terrorism in the World Post 9/11 |

83

|

| On Cecil's Brown's "What Happened to My Black

Studies?" |

84

|

| Has Nature Turned Against America? |

87

|

| America, the Fire This Time |

89

|

| Black Studies, Treading Water |

90

|

| Beyond the Ignorance Zone |

91

|

| Bush, Last American Tragedy |

92

|

|

Farrakhan's Final Call |

94

|

| Mass Murder in the Middle East and the Peace

Movement |

95

|

| Michael Rode His Boat Ashore |

97

|

| Minister of Poetry Brings Tears to Sacramento |

97

|

| MMinister

of Poetry Replies to Dr. Julia Hare |

99

|

| War in Iraq |

100

|

| Of Spiritual Things |

104

|

|

|

| Chapter Four:

Crazy House of the Negro Book Tour |

107

|

| Open Letter to the Poets of Detroit |

109

|

| Human Earthquake Rocks New York City |

110

|

| Marvin X, Sonia Sanchez and the Crazy House Band |

112

|

| Live in Philly at Warm Daddies |

113

|

| Speaks to the Gullah Nation, South Carolina |

114

|

| Human Earthquake Hits Houston, Texas |

116

|

| Call for General Strike at Reparation Rally |

118

|

|

|

| Chapter Five: Of Myth and Rituals |

121

|

| Hero/Shero Defined |

123

|

|

Islam Needs a Martin Luther |

124

|

| End of World Innocence |

127

|

| Hug a Thug: The Education of Ptah Allah-El |

128

|

| Throws in Poetry Towel |

132

|

| Mass Murder in Fresno, CA |

133

|

| Life in Social Movements |

135

|

| What Is Life and Why Are We Living |

136

|

|

Of Men Beast, Ancestors and Nature |

137

|

| Black Woman's Tit Knocks Out America |

138

|

| Gay Marriage and Black Liberation |

139

|

| New Nat Turner |

142

|

| Happy New Year, 2003 |

146

|

| Twisted Route of Peace March |

147

|

|

|

| Chapter Six: Reviews and Blues |

149

|

| Film Review: Ray |

151

|

| Book Review: How to Find a BMW by Julia Hare |

154

|

| Book Review: America's Still the Place, Charlie

Walker |

161

|

| Book Review: Somebody Blew Up America, Amiri Baraka |

163

|

| Movie Review: Gospel of the Game, James Robinson |

169

|

| Book Review: Wounded in the House of a Friend, Sonia

Sanchez |

174

|

| Drama Review: Pantalos and Collard Greens |

`179 |

| Drama Review: Invisible Chains |

186

|

| Movie Review: Panther in Africa |

190

|

|

|

| Chapter Seven: Blackness and Nothingness |

194

|

| Am I Black, Am I White |

200

|

|

Black Bourgeoisie Defend Their Own |

202

|

|

The Meaning of Black Reconstruction |

203

|

|

Black Reconstruction, Week Two |

205

|

| Black Reconstruction, Week Three |

207

|

|

Negro Psychosexuality in the Post Crack Society |

209

|

| Black Muslims as Fifth Column in US |

211

|

|

VIP Nigguhs and Rape

|

212

|

| Powell, the Running Dog, Raps |

213

|

| Fable of the Horse, the Cow, the Bull |

215

|

| Power of Prayer |

217

|

|

|

Wish I Could Tell You the Truth i

s

available from Black Bird Press, 11132 Nelson Bar Road, Cherokee

CA 95965, 19.95. Or email Marvin --

mrvnx@yahoo.com